SEARCH THE ENTIRE SITE

Interview with Chalisée Naamani

Your work is characterised by assemblages of materials, symbols, and images. Can you tell us more about your practice?

Chalisée Naamani:I create what I like to call “image-garments.” They are real garments, with cuts, seams, and finishing touches, but they are not meant to be worn. They’re more like sculptures.

I draw heavily on fashion history, but I don’t limit myself to clothing in the strict sense. For example, in this exhibition, I worked with the form of a punching bag, which interested me as a symbolic object.

I use reclaimed materials, which I combine with textile prints. Over time, I’ve built up a huge image bank made up of photos taken on my phone, screenshots from the internet, things I’ve spotted in the street. I print them onto fabric, but also onto objects and accessories that complete the pieces.

For this exhibition, I also sewed a large puzzle rug reminiscent of a baby’s play mat. I had a baby a year ago, and of course, that’s influenced my perspective. The rug connects the very beginning of motor development—the first movements of a child—with the idea of gradually building yourself up. At the moment, my son is copying my gestures. That ties in with one of my aesthetic obsessions: imitation, replication. People often talk about it negatively, but it’s the foundation of all learning.

It’s also deeply rooted in the history of textiles: counterfeiting developed alongside the Industrial Revolution, with the first large-scale reproduction techniques. What is a copy? What is an original? And at what point does an image become valuable?

How does your family history influence your work?

CN:I’m Franco-Iranian, and for this exhibition I drew on that cultural heritage and my family’s history. There are quite a few suitcases featured in the exhibition. For me, the suitcase is a powerful image: it speaks of transport, transition, but also of transmission. What we choose to take with us, what we leave behind, what we carry from one country to another, from one generation to the next. Some of these suitcases are covered in tulip prints—my favourite flower, but also one that holds deep symbolic meaning in Iran. The government adopted it as a symbol of martyrdom, with the idea that red tulips are nourished by the blood of martyrs. That’s the official iconography—but what interests me more is what it says about exile, migration, and those we forget, or conversely, those we elevate to the status of heroes and heroines.

This exhibition is also closely tied to my grandfather, who was involved in a traditional Iranian sport called Varzesh-e Pahlavani.

It’s an ancient sport, now overseen by a federation, but it’s said to have originally been prac-tised in secret underground spaces during the Arab-Muslim invasion in the 7th century. Men would gather to train for combat, but the practice also involved chanting and prayer. It was both a form of physical and cultural resistance.

This sport is practised in a space known as the zurkhaneh, literally “the house of strength.” The architecture plays an important symbolic role: you enter through a low door, which requires a gesture of humility, and the space is typically octagonal in shape.

Is that where the title of your exhibition comes from?

CN:Yes, that’s exactly it. The zurkhaneh is a kind of octagonal pit, dug about a metre deep. When I first visited the space where the exhibition would take place, I was immediately struck by the rows of steps leading downwards. They unintentionally echoed the layout of a zurkhaneh. That became the starting point for my project.

As I dug a little deeper, I discovered that the octagon is a shape found in Renaissance bap-tisteries, but also in Islamic iconography—especially eight-pointed stars, which are very common in architecture. And then, more recently, in pop culture, there was the infamous “octogone” between Booba and Kaaris—the MMA fight between the two rappers that never actually happened, but which turned the word into popular slang for a showdown.

It also gave me a way into exploring ideas around masculinity and virility. The zurkhaneh was originally a male-only space. But today, through social media, I see that women in Iran are reclaiming those spaces for themselves.

You also reference political movements in your exhibition. It includes Women, Life, Freedom as well as a nod to the Yellow Vests.

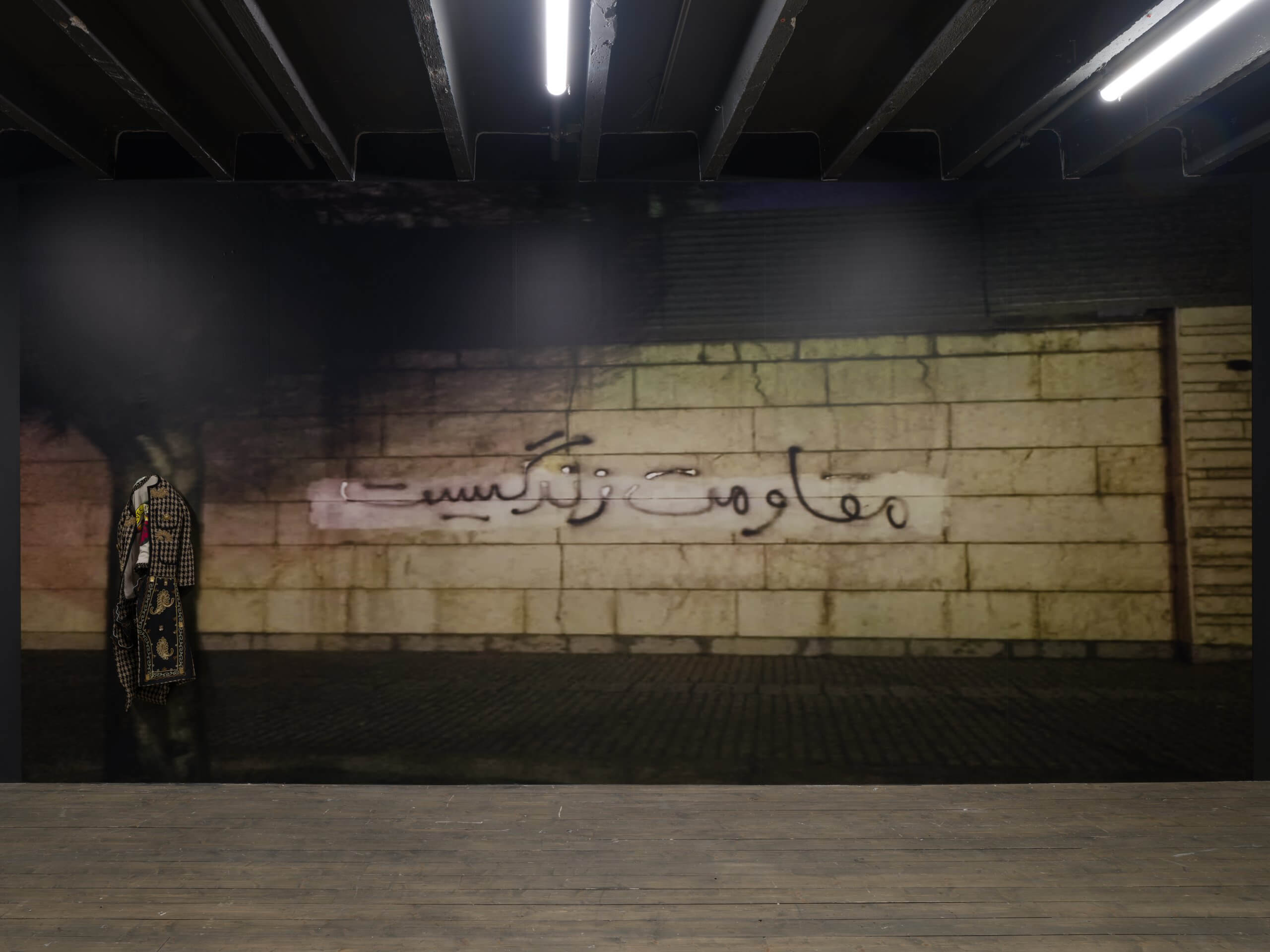

CN:For the exhibition, I created a wallpaper based on a photo taken anonymously in Iran during the Woman, Life, Freedom movement and relayed on social networks.. It shows a slogan in Farsi painted on a wall—a very poetic phrase, difficult to translate, but roughly meaning: “To live is to resist.”

The photo was taken spontaneously. It’s very pixelated, but I used it as it was. You can see a white strip across it, because the government was repainting over the graffiti—though that didn’t stop protesters from returning to rewrite the message over it. That speaks directly to the idea of cultural resistance, which is central to the exhibition.

As for the Yellow Vests, back when I was preparing for my degree show, I used to pass a luxury brand advert every morning. It showed an annoyingly pristine image of a white couple, dressed in white, standing in a completely white landscape. Then one morning, someone had spray-painted a fluorescent yellow vest onto their cashmere jumpers.

Since I’m very interested in fashion history, I found it fascinating that a social movement had taken the name of a garment. Digging a little deeper, I found out that the technical term for a yellow vest is high-visibility garment. That made me think of the invisibility cloak in the Harry Potter series — except this would be the opposite: a cloak of maximum visibility for people who have been rendered invisible.

So, I sewed a kind of cape from a fluorescent yellow tracksuit, covering it with symbolic elements. One of them is the Madonna of Mercy by Piero della Francesca depicted in a long cloak that tells the entire story of the Bible. I liked the idea of a garment functioning as a book—or rather, as a comic strip. In the Middle Ages, iconographic vocabulary was used to convey the Bible to people who couldn’t read.

Religious iconography features heavily in your work.

CN:Yes, I think it’s simply because I’ve looked at a lot of painting over the years. And religious painting was one of my first aesthetic shocks. In some of my pieces, I’ve even borrowed the structure of polyptychs—those painted panels that open up to tell a story in several parts. I also love the baroque side of things—that sense of excess, of flamboyance, even something bordering on bling—whether in painting, clothing, or architecture.

What interests me too is the use of perspective that developed during the Renaissance. It’s a very Western way of constructing the world: linear, hierarchical, individualistic.

By contrast, in Persian miniatures, there’s no single-point perspective. Everything happens at once. A single scene can hold ten events. There’s neither depth nor hierarchy. That’s more or less how my thinking—and my exhibition—works : several threads running in parallel, coexisting without necessarily aiming for order. It’s a different way of seeing the world and telling stories.